Appendix J — Solving Initial-Value ODEs

This appendix examines the numerical solution of sets of initial value ordinary differential equations (IVODEs). There are many software packages that include an IVODE solver (a function that can be used to solve sets of IVODEs). While the details differ between software packages, almost all IVODE solvers require the same input and they return essentially the same results. This appendix provides sufficient information for readers to follow Reaction Engineering Basics examples and to solve sets of IVODEs using the IVODE solver they prefer. Readers seeking a more complete understanding of how IVODE solvers work should consult a numerical methods reference book or take a course on numerical methods.

J.1 Identifying IVODEs and Preparing to Solve Them Numerically

A differential equation contains at least one derivative. A distinguishing feature of a set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) is that every derivative that appears in the equations has the same independent variable. Put differently, there are no partial derivatives in a set of ordinary differential equations. In virtually all cases, the sets of IVODEs that are solved in Reaction Engineering Basics are linear, first-order ODEs. That means that there are no higher order derivatives in the equations and that there are no products, quotients or powers of the first-order derivatives.

Most generally, the sets of IVODEs under consideration here will take the form shown in Equations J.1 through J.4. In those equations \(x\) is the independent variable; \(y_1\), \(y_2\), \(y_3\), and \(y_4\) are the dependent variables; and \(m_{1,1}\) through \(m_{4,4}\) and \(g_1\) through \(g_4\) can be constants (including zero) or functions of the independent and dependent variables.

\[ m_{1,1}\frac{dy_1}{dx} + m_{1,2}\frac{dy_2}{dx} + m_{1,3}\frac{dy_3}{dx} + m_{1,4}\frac{dy_4}{dx} = g_1 \tag{J.1}\]

\[ m_{2,1}\frac{dy_1}{dx} + m_{2,2}\frac{dy_2}{dx} + m_{2,3}\frac{dy_3}{dx} + m_{2,4}\frac{dy_4}{dx} = g_2 \tag{J.2}\]

\[ m_{3,1}\frac{dy_1}{dx} + m_{3,2}\frac{dy_2}{dx} + m_{3,3}\frac{dy_3}{dx} + m_{3,4}\frac{dy_4}{dx} = g_3 \tag{J.3}\]

\[ m_{4,1}\frac{dy_1}{dx} + m_{4,2}\frac{dy_2}{dx} + m_{4,3}\frac{dy_3}{dx} + m_{4,4}\frac{dy_4}{dx} = g_4 \tag{J.4}\]

While four equations are being used here for illustration purposes, there can be any number of ordinary differential equations in the set as long as the number of ordinary differential equations is equal to the number of dependent variables, and there is only one independent variable. In Reaction Engineering Basics, the independent variable is either the elapsed time, \(t\), or the axial position, \(z\), measured from the inlet of a plug flow reactor.

A set of \(N\) initial-value ordinary differential equations will contain 1 independent variable and \(N\) dependent variables. The other quantities that may appear within the \(m_{i,j}\) coefficients and \(g_j\) functions are (a) constants, (b) the independent variable, (c) the dependent variables, (d) known constants, and (e) other unknowns. Before the set of IVODEs can be solved, the other unknowns must be calculated or provided as described subsequently.

What distinguishes the equations as IVODEs is that they value of each dependent variable, \(y_j\), is known at the point where \(x\) is equal to zero and the value of either \(x\) or one of the \(y_j\) is known at some other point. The values of the dependent variables at \(x\) = 0 are called the initial values. The variable (\(x\) or one of the \(y_j\)) that is known at some other point together with that known value is called the stopping criterion for reasons described below.

In preparation for solving a set of \(N\) IVODEs, they should be rearranged into a set of derivative functions if they aren’t already in that form. For example, Equations J.1 through J.4 need to be converted to derivative expressions of the form shown in Equations J.5 through J.8 where \(f_1\), \(f_2\), \(f_3\), and \(f_4\) each may be a function of \(x\), \(y_1\), \(y_2\), \(y_3\), and \(y_4\) and may also contain known constants and other unknowns that must be calculated or provided before the IVODEs can be solved numerically.

\[ \frac{dy_1}{dx} = f_1 \tag{J.5}\]

\[ \frac{dy_2}{dx} = f_2 \tag{J.6}\]

\[ \frac{dy_3}{dx} = f_3 \tag{J.7}\]

\[ \frac{dy_4}{dx} = f_4 \tag{J.8}\]

That can be accomplished by algebraic manipulation of Equations J.1 through J.4, but it is particularly straightforward if the original IVODEs are written as a matrix equation. The coefficients in Equations J.1 through J.4, \(m_{1,1}\), \(m_{1,2}\), etc., can be used to construct a so-called mass matrix, \(\boldsymbol{M}\), as shown in Equation J.9, the dependent variables can be used to construct a column vector, \(\underline{y}\), as in equation Equation J.10, and the functions, \(g_1\), \(g_2\), \(g_3\), and \(g_4\), can be used to construct a column vector, \(\underline{g}\), as in equation Equation J.11.

\[ \boldsymbol{M} = \begin{bmatrix} m_{1,1} \ m_{1,2} \ m_{1,3} \ m_{1,4} \\m_{2,1} \ m_{2,2} \ m_{2,3} \ m_{2,4} \\m_{3,1} \ m_{3,2} \ m_{3,3} \ m_{3,4} \\ m_{4,1} \ m_{4,2} \ m_{4,3} \ m_{4,4} \end{bmatrix} \tag{J.9}\]

\[ \underline{y} = \begin{bmatrix} y_1 \\ y_2 \\ y_3 \\ y_4 \end{bmatrix} \tag{J.10}\]

\[ \underline{g} = \begin{bmatrix} g_1 \\ g_2 \\ g_3 \\ g_4 \end{bmatrix} \tag{J.11}\]

Equations J.1 through J.4 then can be written as a matrix equation, Equation J.12. Pre-multiplying each side of Equation J.12 by the inverse of the mass matrix yields the desired derivative expressions, Equation J.13. That is, comparing Equation J.13 to Equations J.5 through J.8, it is apparent that they are equivalent with \(f_1\), \(f_2\), \(f_3\), and \(f_4\) given by Equation J.14.

\[ \boldsymbol{M}\frac{d}{dx}\underline{y} = \underline{g} \tag{J.12}\]

\[ \frac{d}{dx}\underline{y} = \boldsymbol{M}^{-1} \underline{g} \tag{J.13}\]

\[ \begin{bmatrix} f_1 \\ f_2 \\ f_3 \\ f_4 \end{bmatrix} = \underline{f} = \boldsymbol{M}^{-1} \underline{g} \tag{J.14}\]

J.2 IVODE Solvers

An IVODE solver is a computer function that solves a set of IVODEs numerically. Typically it must be provided with the following inputs: (a) the initial value of the independent variable, (b) the corresponding initial value of each dependent variable, (c) the identity of the variable (independent or one of the dependents) that is known at another point, (d) the known final value of that variable, and (e) a derivatives function. The IVODE solver returns sets of corresponding values of the independent variable and each of the dependent variables spanning the range from their initial value to the point where the stopping criterion was satisfied.

The inner workings of IVODE solvers are beyond the scope of Reaction Engineering Basics. Nonetheless, a simplified understanding of how IVODEs are solved numerically is useful. When an IVODE solver is called, it must be provided with the following arguments: the initial values, the stopping criterion (i. e. the final value of either the independent variable or one of the dependent variables), and a derivatives function. As described below, the derivatives function uses the IVODEs to calculate and return the values of the derivatives appearing in the IVODEs.

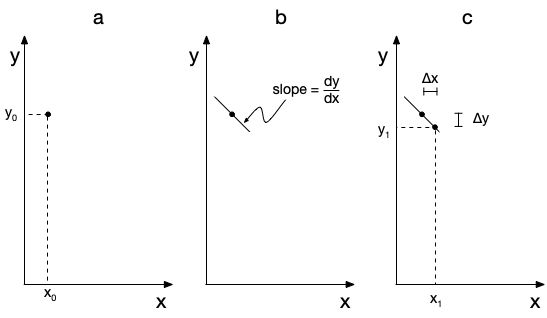

The solver starts from the initial values, as illustrated graphically in part (a) of Figure J.1 for any one of the dependent variables. It isn’t possible to plot \(y\) vs. \(x\) at that point because \(y\left(x\right)\) is not known. (Indeed, \(y\left(x\right)\) is the solution to the IVODE.) Instead, the solver uses the IVODEs to calculate the value of each of the derivatives at \(\left(x_0,y_0\right)\). The derivative, \(\frac{dy}{dx}\), at that point is the slope of the unknown function at \(\left(x_0,y_0\right)\). This is shown graphically in part (b) of Figure J.1.

Starting from the known point, \(\left(x_0,y_0\right)\), the solver increases \(x\) by a small amount, \(\Delta x\), which is known as the step-size. It then calculates the corresponding change in \(y\), \(\Delta y\), using the slope. The resulting point, \(\left(x_1,y_1\right)\), is shown in part (c) of Figure J.1. This process is sometimes referred to as taking an integration step. Effectively, the solver uses the small straight line segment between \(\left(x_0,y_0\right)\) and \(\left(x_1,y_1\right)\) to approximate the true solution, \(y\left(x\right)\), in that interval. The accuracy of this approximation increases as \(\Delta x\) decreases, so typically the solver uses small steps. A new integration step is then taken starting fr0m \(\left(x_1,y_1\right)\).

Of course, the solver eventually must stop taking integration steps. After completing each step, the solver checks to determine whether making that step resulted in the stopping criterion being satisfied. If not, the solver takes another integration step. As an example, suppose the stopping criterion is that \(y_3\) should equal some value, \(y_{3,f}\), the solver would check to see whether \(y_3\) did, in fact, reach or surpass \(y_{3,f}\) after making the step. In most cases the stopping criterion will have been surpassed by some small amount, in which case the solver interpolates to find final values that exactly satisfy the stopping criterion. It then returns the values of the dependent variables and the independent variable for all of the steps it took while solving the IVODEs, including those final interpolated values.

J.2.2 The Derivatives Function

The IVODE solver is part of a mathematics software package. It must call the derivatives function which is written by the engineer who needs to solve a set of IVODEs. While the arguments to derivatives function are always a value of the independent variable and the corresponding values of each of the dependent variables, and while the return values are always the values of each of the derivatives that appear in the IVODEs, the details of how the arguments are provided and the return values returned is specifice by the mathematics software package. The engineer calling the IVODE solver must write the derivatives function so it conforms to those specifications.

The calculations perfromed within the derivarives function are straightforward. It receives values for the independent and dependent variables, and any known constants that appear in the IVODEs are available. If there are any other unknowns in the IVODEs, their values are first calculated. In most cases these quantities can be calculated using the independent variable, the dependent variables, and known constants. However, if it is not possible to calculate any of the other unknowns appearing in the IVODEs, they must be provided to the derivatives function.

Providing unknown constants to the residuals function forces a computer programming choice like that described in Appendix I for the residuals function. The issue is that the other unknowns cannot be passed to the derivatives function as arguments. The arguments that can be passed to the derivatives function are fixed by the mathematics software package being used and are limited to values of the independent and dependent variables. As a consequence, any other unknowns that cannot be calculated within the derivatives function will need to be provided by other means. The documentation for the mathematics software package may suggest a preferred way to do this such as by using a global variable or by using a pass-through function. Once the other constants are calculated or made available, all that remains to be done within the derivatives function is to evaluate the derivatives using the derivatives functions described above and return them.

J.3 Mathematical Formulation of the Numerical Solution of a Set of IVODEs

Once a set of \(N\) IVODEs containing \(N\) dependent variables has been identified, the initial values have been defined, and a stopping criterion has been specified, the numerical solution of the IVODEs can be formulated. The first step is to formulate the derivatives function. The derivatives function specification should list the arguments to be passed to it (values of the independent and dependent variables), the quantities it will return (values of each of the derivatives appearing in the set of IVODEs), and any other quantities that must be provided to it by means other than as an argument. The formulation of the derivatives function should next present the algorithm, that is, the sequence of calculations need to evaluate and return the values of the derivatives assuming the given and known constants, arguments, and additional required input are available.

The remainder of the formulation focuses on the IVODE solver. It begins by showing how to calculate any unknown initial and final values. Next, any other unknowns that cannot be calculated within the derivatives function should be made available to it as described above. After that, the IVODE solver should be called. The formulation should list the arguments to be passed to it (initial values, stopping criterion, and the derivatives function) and the quantities it will return (corresponding sets of values of the independent and dependent values spanning the range from their initial values to the point where the stopping criterion is satisfied). That completes the mathematical formulation of the numerical solution of a set of IVODEs.

J.4 Example

The following example illustrates the formulation of the numerical solution of a set of IVODEs.

J.4.1 Example: Formulation of the Solution of a Set of BSTR Design Equations

A reaction engineer needs to solve the BSTR design equations shown in equations (1) and (2). The initial values and stopping criterion are shown in Table J.1. The gas constant, \(R\), reactor volume, \(V\), final time, \(t_f\), and initial concentration of A, \(C_{A,0}\) are known constants. The Arrhenius pre-exponential factor, \(k_0\), and activation energy, \(E\), are constants, but they cannot be calculated from the information that will be available to the derivatives function. Formulate the numerical solution of equations (1) and (2).

\[ \frac{dn_A}{dt} = -rV \tag{1} \]

\[ \frac{dn_Z}{dt} = rV \tag{2} \]

\[ r = kC_A \tag{3} \]

\[ k = k_0 \exp{\left( \frac{-E}{RT}\right)} \tag{4} \]

\[ C_A = \frac{n_A}{V} \tag{5} \]

\[ n_{A,0} = C_{A,0}V \tag{6} \]

| Variable | Initial Value | Stopping Criterion |

|---|---|---|

| \(t\) | \(0\) | \(t_f\) |

| \(n_A\) | \(n_{A,0}\) | |

| \(n_Z\) | \(0\) |

Derivatives Function

\(\qquad\) Arguments: \(t\), \(n_A\), and \(n_Z\).

\(\qquad\) Other input: \(k_0\) and \(E\).

\(\qquad\) Return values: \(\frac{dn_A}{dt}\) and \(\frac{dn_Z}{dt}\)

\(\qquad\) Algorithm:

\(\qquad \qquad\) 1. Calculate other unknowns.

\[ k = k_0 \exp{\left( \frac{-E}{RT}\right)} \tag{4} \]

\[ C_A = \frac{n_A}{V} \tag{5} \]

\[ r = kC_A \tag{3} \]

\(\qquad \qquad\) 2. Evaluate and return the derivatives using equations (1) and (2).

Solving the Design Equations

- Calculate the unknown initial and final values

\[ n_{A,0} = C_{A,0}V \tag{6} \]

Make \(k_0\) and \(E\) available to the derivatives function.

Call an IVODE solver.

Pass the initial values, stopping criterion and the name of the derivatives function as arguments.

receive corresponding sets of values of \(t\), \(n_A\), and \(n_Z\) spanning the range from \(t=0\) to \(T=t_f\).

J.5 Symbols Used in Appendix J

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| \(f_i\) | Function of the independent and dependent variables in the \(i^{th}\) differential equation when the ODEs are written in vector form without a matrix. |

| \(\underline f\) | Column vector formed from a set of functions. |

| \(g_i\) | Function of the independent and dependent variables in the \(i^{th}\) differential equation when the ODEs are written using a matrix. |

| \(\underline g\) | Column vector formed from a set of functions. |

| \(k\) | Rate coefficient. |

| \(k_0\) | Arrhenius pre-exponential factor. |

| \(m_{i,j}\) | Coefficient that multiplies the derivative of dependent variable \(j\) in the \(i^{th}\) differential equation. |

| \(n_i\) | Molar amount of reagent \(i\), an additional subscripted ‘\(0\)’ denotes the initial amount. |

| \(r\) | Reaction rate per unit volume. |

| \(t\) | Time; a subscripted \(f\) indicates the final time. |

| \(x\) | Generic independent variable; a subscripted \(0\) indicates the initial value. |

| \(\left(x_i,y_i\right)\) | Cartesion coordinates of the \(i^{th}\) point. |

| \(y\) | Generic dependent variable; a numerical subscript denotes one specific dependent variable out of the vector \(\underline y\); an additional subscripted \(f\) indicates the final value; an additional subscripted \(0\) indicates the initial value. |

| \(\underline y\) | Column vector formed from the dependent variables in a set of ODEs. |

| \(z\) | axial position measured from the reactor inlet. |

| \(C_i\) | Concentration of reagent \(i\), an additional subscripted ‘\(0\)’ denotes the initial concentration. |

| \(E\) | Activation energy. |

| \(\boldsymbol{M}\) | Matrix of coefficients that multiplies a column vector of derivatives when the ODEs are written as a matrix equation. |

| \(N\) | Number of IVODEs in the set. |

| \(R\) | Ideal gas constant. |

| \(T\) | Temperature; a subscripted \(in\) denotes the inlet temperature. |

| \(V\) | Volume of fluid. |

| \(\Delta x\) | Change in the value of the independent variable. |

| \(\Delta y\) | Change in the value of the dependent variable. |