Appendix H — Axial Dispersion Reactor Models

This appendix starts with the mole and energy balances for an ideal PFR. It adds dispersion terms to allow for mixing of heat and mass in the axial direction, leading to one form of the transient axial dispersion reactor design equations. In anticipation of solving the steady-state versions of those equations numerically, it then shows how the steady state axial dispersion mole and energy balances can be rewritten as an equivalent set of first-order differential equations. Conventionally the axial dispersion model is written using the superficial velocity of the fluid in the \(z\) direction, \(u_z\), but for consistency with the other chapters in Reaction Engineering Basics it is written here in terms of the volumetric flow rate.

H.1 Axial Dispersion Reactor Design Equations

The transient mole and energy balances for a PFR are derived in Appendix G. They serve as the starting point for the derivation of the axial dispersion reactor design equations. The assumption of plug flow is retained in the axial dispersion model. The only modification to the PFR mole and energy balances is addition of the term, \(-D_{ax} \frac{\pi D^2}{4} \frac{d^2C_i}{dz^2}\), to the ideal PFR mole balance, and the term, \(-\lambda_{ax} \frac{\pi D^2}{4} \frac{d^2T}{dz^2}\), to the ideal PFR reacting fluid energy balance.

H.1.1 The Transient Axial Dispersion Mole Balance

The generation of the axial dispersion mole balance begins with ideal PFR mole balance.

\[ \frac{\pi D^2}{4\dot V} \frac{\partial\dot n_i}{\partial t} - \frac{\pi D^2\dot n_i}{4\dot V^2} \frac{\partial \dot V}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial \dot n_i}{\partial z} = \frac{\pi D^2}{4}\sum_j \nu_{i,j}r_j \]

The dispersion term is added, noting that because \(C_i\) varies with both \(t\) and \(z\), it uses a partial derivative.

\[ \frac{\pi D^2}{4\dot V} \frac{\partial\dot n_i}{\partial t} - \frac{\pi D^2\dot n_i}{4\dot V^2} \frac{\partial \dot V}{\partial t} - D_{ax} \frac{\pi D^2}{4} \frac{\partial ^2C_i}{\partial z^2} + \frac{\partial \dot n_i}{\partial z} = \frac{\pi D^2}{4}\sum_j \nu_{i,j}r_j \]

This presents a dilemma because the concentration, \(C_i\), is the dependent variable in the axial dispersion term, but the molar flow rate, \(\dot{n}_i\), is the dependent variable in the ideal PFR mole balance. Consequently, either the dispersion term must be rewritten in terms of the molar flow rate, or the molar flow rate must be rewritten in terms of the concentration. Practically, the axial dispersion mole balance is much more tractable when it is written using the concentration as the dependent variable, so the terms including the molar flow rate need to be re-expressed in terms of the concentration. To do so, both sides of the equation first are multiplied by by \(\frac{4}{\pi D^2}\).

\[ \frac{1}{\dot V} \frac{\partial\dot n_i}{\partial t} - \frac{\dot n_i}{\dot V^2} \frac{\partial \dot V}{\partial t} - D_{ax} \frac{\partial ^2C_i}{\partial z^2} + \frac{4}{\pi D^2} \frac{\partial \dot n_i}{\partial z} = \sum_j \nu_{i,j}r_j \]

Noting that \(C_i = \frac{\dot{n}_i}{\dot{V}}\), and consequently \(\frac{\partial C_i}{\partial t} = \frac{1}{\dot V} \frac{\partial\dot n_i}{\partial t} - \frac{\dot n_i}{\dot V^2} \frac{\partial \dot V}{\partial t}\), facilitates conversion of the dependent variable in the time derivatives.

\[ \frac{\partial C_i}{\partial t} - D_{ax} \frac{\partial ^2C_i}{\partial z^2} + \frac{4}{\pi D^2} \frac{\partial \dot n_i}{\partial z} = \sum_j \nu_{i,j}r_j \]

Similarly noting that \(\dot{n}_i\) = \(\dot{V} C_i\) eliminates the molar flow rate as the dependent varibles in the \(z\) derivative.

\[ \frac{\partial C_i}{\partial t} - D_{ax} \frac{\partial ^2C_i}{\partial z^2} + \frac{4}{\pi D^2} \frac{\partial }{\partial z}\left( \dot{V} C_i \right) = \sum_j \nu_{i,j}r_j \]

Applying the chain rule for differentiation then yields the desired form of the mole balance

\[ \frac{\partial C_i}{\partial t} - D_{ax} \frac{\partial ^2C_i}{\partial z^2} + \frac{4 \dot{V}}{\pi D^2} \frac{\partial C_i}{\partial z} + \frac{4 C_i}{\pi D^2} \frac{\partial \dot{V}}{\partial z} = \sum_j \nu_{i,j}r_j \]

H.1.2 The Transient Axial Dispersion Energy Balance

The generation of the energy balance begins with the ideal PFR energy balance.

\[ \begin{align} \frac{\pi D^2}{4 \dot{V}} \left( \sum_i \dot{n}_i\hat{C}_{p,i} \right)& \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} - \frac{\pi D^2}{4} \frac{\partial P}{\partial t} + \left( \sum_i \dot{n}_i\hat{C}_{p,i} \right)\frac{\partial T}{\partial z} \\&= \pi DU\left( T_{ex} - T \right) - \frac{\pi D^2}{4} \sum_j r_j\Delta H_j \end{align} \]

The dispersion term is added, again noting that because \(T\) varies with both \(t\) and \(z\), a partial derivative is used.

\[ \begin{align} \frac{\pi D^2}{4 \dot{V}} \left( \sum_i \dot{n}_i\hat{C}_{p,i} \right)& \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} - \frac{\pi D^2}{4} \frac{\partial P}{\partial t} -\lambda_{ax} \frac{\pi D^2}{4} \frac{d^2T}{dz^2} + \left( \sum_i \dot{n}_i\hat{C}_{p,i} \right)\frac{\partial T}{\partial z} \\&= \pi DU\left( T_{ex} - T \right) - \frac{\pi D^2}{4} \sum_j r_j\Delta H_j \end{align} \]

Both sides of the equation can then be multiplied by \(\frac{4}{\pi D^2}\).

\[ \begin{align} \frac{1}{\dot{V}} \left( \sum_i \dot{n}_i\hat{C}_{p,i} \right)& \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} - \frac{\partial P}{\partial t} - \lambda_{ax} \frac{d^2T}{dz^2} + \frac{4}{\pi D^2} \left( \sum_i \dot{n}_i\hat{C}_{p,i} \right)\frac{\partial T}{\partial z} \\&= \frac{4U}{D} \left( T_{ex} - T \right) - \sum_j r_j\Delta H_j \end{align} \]

Again noting that \(\dot{n}_i\) = \(\dot{V} C_i\) allows elimination of the molar flow rate, and after doing so, \(\dot{V}\) can be factored out of the summations yielding the desired form of the axial dispersion energy balance.

\[ \begin{align} \left( \sum_i C_i\hat{C}_{p,i} \right)& \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} - \frac{\partial P}{\partial t} - \lambda_{ax} \frac{d^2T}{dz^2} + \frac{4\dot{V}}{\pi D^2} \left( \sum_i C_i\hat{C}_{p,i} \right)\frac{\partial T}{\partial z} \\&= \frac{4U}{D} \left( T_{ex} - T \right) - \sum_j r_j\Delta H_j \end{align} \]

H.1.3 The Steady-State Axial Dispersion Reactor Design Equations.

When the reactor operates at steady state, all of the time derivatives are equal to zero, and the spatial derivatives become ordinary derivatves.

\[ - D_{ax} \frac{d^2C_i}{dz^2} + \frac{4 \dot{V}}{\pi D^2} \frac{dC_i}{dz} + \frac{4 C_i}{\pi D^2} \frac{d\dot{V}}{dz} = \sum_j \nu_{i,j}r_j \]

\[ - \lambda_{ax}\frac{d^2 T}{d z^2} + \frac{4 \dot{V}}{\pi D^2} \left(\sum_i C_i \hat{C}_{p,i}\right) \frac{d T}{d z} = \frac{4U}{D}\left(T_{ex} - T\right) - \sum_j r_j \Delta H_j \]

The two design equations above contain three dependent variables, \(C_i\), \(T\), and \(\dot{V}\), so an additional design equation is needed or a dependent variable must be eliminated. If the reacting fluid is an incompressible liquid, then the volumetric flow rate does not change and it’s derivative with respect to \(z\) in the mole balance can be set equal to zero. This would apply when the reacting fluid is a liquid and when the reacting fluid is an ideal gas in an isothermal, isobaric reactor where the total number of moles does not change as the reactions occur.

\[ \frac{d\dot{V}}{dz} = 0 \qquad \text{liquids, ideal gases at constant }T, P, \text{and } \dot{n}_{total} \]

More generally for gas phase reactants, the mole balances for each of the reagents can be summed, and the total concentration can be expressed in terms of the ideal gas law, \(\left( \sum_i C_i = \frac{P}{RT}\right)\).

\[ - D_{ax} \frac{d^2}{dz^2}\left(\sum_i C_i\right) + \frac{4 \dot{V}}{\pi D^2} \frac{d}{dz}\left(\sum_i C_i\right) + \frac{4}{\pi D^2}\left(\sum_i C_i\right) \frac{d\dot{V}}{dz} = \sum_i\sum_j \nu_{i,j}r_j \]

\[ - D_{ax} \frac{d^2}{dz^2}\left(\frac{P}{RT}\right) + \frac{4 \dot{V}}{\pi D^2} \frac{d}{dz}\left(\frac{P}{RT}\right) + \frac{4P}{\pi D^2 RT} \frac{d\dot{V}}{dz} = \sum_i\sum_j \nu_{i,j}r_j \]

The ideal gas constant can be factored out of the derivatives, leading to an additional design equation.

\[ - D_{ax} \frac{d^2}{dz^2}\left(\frac{P}{T}\right) + \frac{4 \dot{V}}{\pi D^2} \frac{d}{dz}\left(\frac{P}{T}\right) + \frac{4P}{\pi D^2 T} \frac{d\dot{V}}{dz} = R\sum_i\sum_j \nu_{i,j}r_j \qquad \text{ideal gas} \]

H.1.4 Steady-State Axial Dispersion Model Boundary Conditions

The axial dispersion design equations include second derivatives of the concentrations and temperature and the first derivative of the volumetric flow rate. Solving them then requires two boundary conditions for each of the concentrations and for the temperature and one boundary condition for the volumetric flow rate. There are a few different ways to write the boundary conditions. The Danckwerts boundary conditions will be presented here.

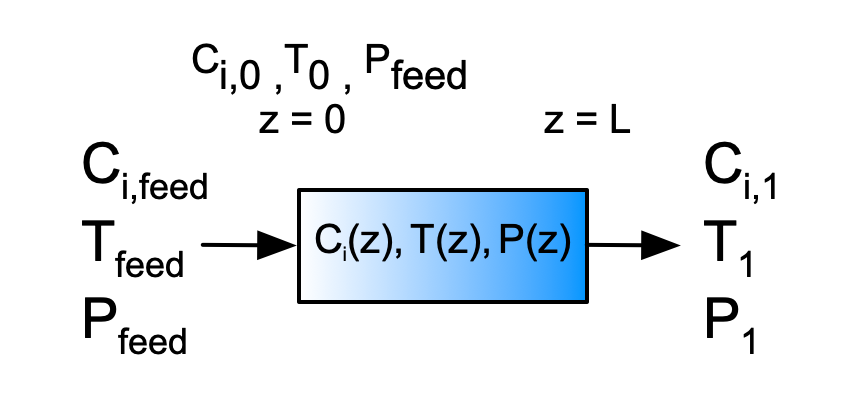

The Danckwerts boundary conditions assume that upstream from the reactor inlet, the flow of each reagent is purely convective. Within the reactor the net flow of each reagent is the combination of convection and the diffusion-like mixing flux. Similar assumptions are made for energy. This is emphasized in Figure H.1 where a subseripted “feed” is used for feed properties, a “0” for properties at the reactor inlet, and a “1” for properties at the reactor outlet.

The Danckwerts boundary conditions simply assume that the purely convective feed flow is equal to the combined convective and flux-like mixing flow at the reactor inlet. Similarly, for the energy balance they assume the purely convective heat flow associated with the feed equals the combined convective flow and conduction-like mixing flux at the reactor inlet.

\[ \dot{V}_{feed}C_{i,feed} = \dot{V}_0 C_{i,0} - D_{ax} \frac{\pi D^2}{4} \frac{dC_i}{dz}\Bigg\vert_{z=0} \]

\[ \dot{V}_{feed}\sum_i\left(C_{i,feed} \hat{C}_{p,i} \right) T_{feed} = \dot{V}_0 \sum_i\left(C_{i,0} \hat{C}_{p,i} \right) T_0 - \lambda_{ax} \frac{\pi D^2}{4} \frac{dT}{dz}\Bigg\vert_{z=0} \]

A second boundary condition is needed for each \(C_i\) and for \(T\). Because the reactor ends at \(z=L\), it can be assumed that the concentrations and temperature will stop changing at that point. Doing so yields the additional boundary conditions.

\[ \frac{dC_i}{dz}\Bigg\vert_{z=L} = 0 \]

\[ \frac{dT}{dz}\Bigg\vert_{z=L} = 0 \]

If the volumetric flow rate is not constant, an additional boundary condition is needed for it.

H.2 Equivalent First-Order, Steady-State Design Equations and Boundary Conditions

When the axial dispersion model is used empirically to model a non-ideal reactor, the derivative of the volumetric flow rate can be set equal to zero. Recognizing that the design equations will be solved numerically, it is useful to rewrite them as an equivalent set of first-order ODEs. This can be accomplished by defining new variables, \(\omega_i\) and \(\omega_T\).

\[ \frac{dC_i}{dz} = \omega_i \]

\[ \frac{dT}{dz} = \omega_T \]

Noting that then \(\frac{d^2C_i}{dz^2} = \frac{d\omega_i}{dz}\) and \(\frac{d^2T}{dz^2} = \frac{d\omega_T}{dz}\), substitution into the second-order design equations converts them to first-order ODEs.

\[ - D_{ax}\frac{d \omega_i}{d z} = - \frac{4 \dot{V}}{\pi D^2}\omega_i + \sum_j \nu_{i,j}r_j \]

\[ - \lambda_{ax}\frac{d \omega_T}{d z} = - \frac{4 \dot{V}}{\pi D^2} \left(\sum_i C_i \hat{C}_{p,i}\right) \omega_T + \frac{4U}{D}\left(T_{ex} - T\right) - \sum_j r_j \Delta H_j \]

The boundary conditions must also be expressed in terms of the new variables. Having dropped \(\frac{d\dot{V}}{dz}\) from the mole balance, it is no longer necessary to differentiate between \(\dot{V}_{feed}\) and \(\dot{V}_0\), in which case substitution in the Danckwerts boundary conditions and rearrangement yields their forms for the equivalent first-order design equations.

\[ C_{i,0} = C_{i,feed} + D_{ax} \frac{\pi D^2}{4\dot{V}} \frac{dC_i}{dz}\Bigg\vert_{z=0} = C_{i,feed} + D_{ax} \frac{\pi D^2}{4\dot{V}} \omega_i\Big\vert_{z=0} \]

\[ \begin{align} T_0 &= \frac{\sum_iC_{i,feed} \hat{C}_{p,i}}{\sum_iC_{i,0} \hat{C}_{p,i}}T_{feed} + \lambda_{ax} \frac{\pi D^2}{4\dot{V} \sum_i\left(C_{i,0} \hat{C}_{p,i} \right)} \frac{dT}{dz}\Bigg\vert_{z=0} \\&= \frac{\sum_iC_{i,feed} \hat{C}_{p,i}}{\sum_iC_{i,0} \hat{C}_{p,i}}T_{feed} + \lambda_{ax} \frac{\pi D^2}{4\dot{V} \sum_i\left(C_{i,0} \hat{C}_{p,i} \right)} \omega_T\Big\vert_{z=0} \end{align} \]

Similarly, substitution in the boundary conditions at \(z=L\) yields the equivalent first-order boundary conditions.

\[ \omega_i\Big\vert_{z=L} = 0 \]

\[ \omega_T\Big\vert_{z=L} = 0 \]

The axial dispersion reactor design equations are boundary value ordinary equations (BVODEs) and must be solved using an appropriate solver (see Appendix M).

H.3 Symbols Used in Appendix H

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| \(\dot{n}_i\) | Molar flow rate of reagent \(i\). |

| \(r_j\) | Rate of reaction \(j\). |

| \(t\) | Time. |

| \(z\) | Axial distance from the reactor inlet. |

| \(C_i\) | Concentration of reagent \(i\), an additional subscript denotes the location. |

| \(\hat{C}_{p,i}\) | Molar heat capacity of reagent \(i\). |

| \(D\) | Diameter of the tubular reactor. |

| \(D_{ax}\) | Axial dispersion coefficient. |

| \(L\) | Length of the tubular reactor. |

| \(P\) | Pressure. |

| \(R\) | Ideal gas constant. |

| \(T\) | Temperature, an additional subscript denotes the location. |

| \(T_{ex}\) | Temperature of the heat exchange fluid. |

| \(U\) | Heat transfer coefficient. |

| \(\dot{V}\) | Volumetric flow rate, an additional subscript denotes the location. |

| \(\lambda_{ax}\) | Thermal axial dispersion coefficient. |

| \(\nu_{i,j}\) | Stoichiometric coefficient of reagent \(i\) in reaction \(j\). |

| \(\omega_i\) | Variable equal to the derivitive of \(C_i\) with respect to \(z\). |

| \(\omega_T\) | Variable equal to the derivitive of \(T\) with respect to \(z\). |

| \(\Delta H_j\) | Heat of reaction \(j\). |